Vicissitudes

Pondering over the stories of The Iliad, Burial at Thebes, and The Epic of Gilgamesh I was reminded of a quote by author Lemony Snicket:

“Fate is like a strange, unpopular restaurant filled with odd little waiters who bring you things you never asked for and don’t always like” (Horseradish).

Lemony may be living centuries apart from the likes of Socrates and Homer, but his words ring true. Despite being incredible, larger-than-life characters, the lead characters of these three tales all learn a similar lesson — that no matter how hard they try, there is absolutely no chance of outrunning fate. This essay will attempt to prove that characters like Gilgamesh, Achilles, and Creon, despite their great and unyielding natures, are all forced to bend the knee to external forces, denoting a fatalistic belief system.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a prime example of this, as the poem begins — Gilgamesh is a man without fear, concern, or many aspirations beyond subjugating the city of Uruk:

Surpassing all other kings, heroic in stature, brave scion of Uruk, wild bull on the rampage! Going at the force he was the vanguard, going at the rear, one his comrades could trust! Who is there can rival his kingly standing, and say like Gilgamesh, ‘It is I am the king’? Gilgamesh was his name from the day he was born, two-thirds god and one third human (2).

Gilgamesh, not merely in feats but on a physiological level stands head and shoulders above his fellow man. As a demigod he is unmatched physically or intellectually and as king of Uruk his power exceeds that of anyone in Samaria. It seems at this point that Gilgamesh is very much in control of his destiny, as he chides the advances of a goddess, slays monsters, and does whatever his heart desires. But, after Gilgamesh is forced to deal with the death of his close friend Enkidu, and begins his journey to find eternal life, he is faced with defeat at nearly every turn, first failing Uta-napishti’s trial and finally losing the precious life-giving plant to the serpent. Realizing his fate, Gilgamesh, the greatest hero in Samaria is moved to tears, not by a monster but by the sheer hopelessness of his situation.

“As it turned away it sloughed its skin. Then Gilgamesh sat down and wept, down his cheeks the tears were coursing, …[he spoke] to Ur-shanabi the boatman:

‘Now far and wide the tide is rising. Having opened the channel I abandoned the tools: what thing would I find that served as my landmark? Had I only turned back, and left the boat on the shore!’ (99).

It is here that Gilgamesh is at the end of his journey and must return to his city, not with a plant, or an artifact, or any semblance of immortality but merely with newfound knowledge of the finite nature of his life.

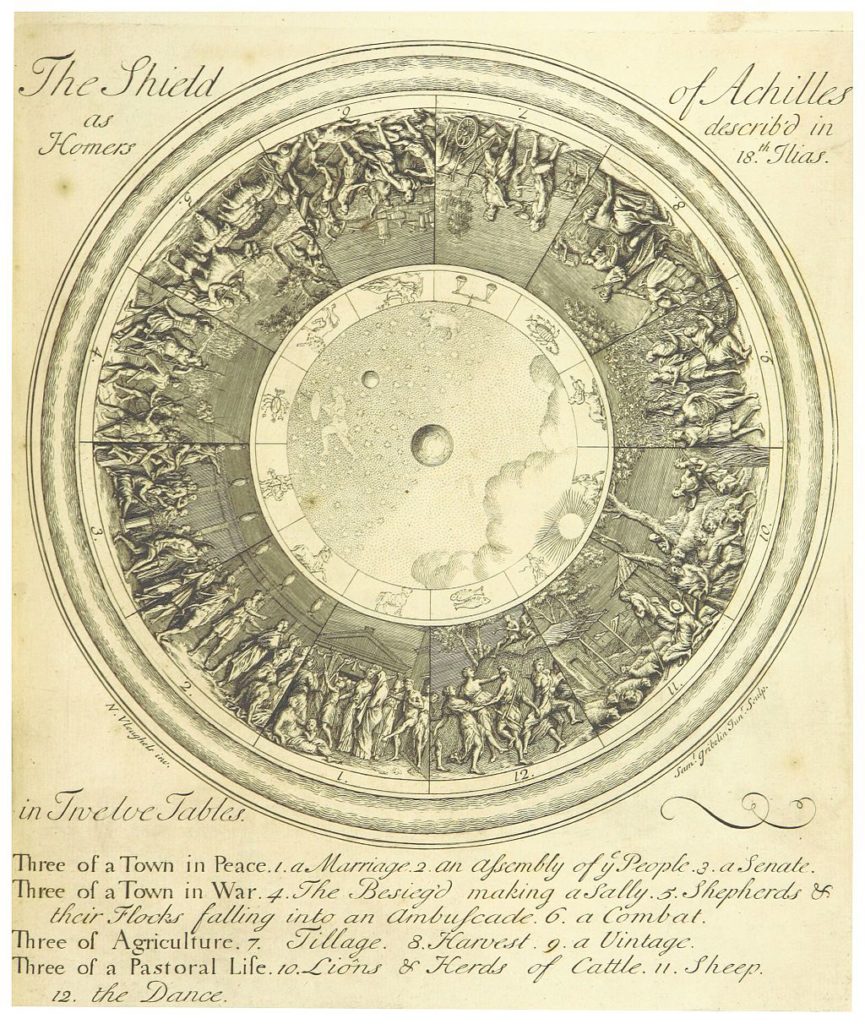

Achilles leads a similar life in Homer’s Iliad, as he is the mightiest warrior of all the Achaeans, a demigod, and a natural born leader. The main difference being that Gilgamesh bowed to no one, while Achilles must answer to the arrogant King Agamemnon for his actions. His separation from both God and man dooms him to a life of loneliness and confusion from which he cannot escape. This comes to a head when Achilles, exiled from his fellow Acheans and torn from his lover Briseis, falls upon his knees and weeps upon the shoreline.

But Achilles wept, and slipping away from his companions, far apart, sat down on the beach of the heaving gray sea and scanned the endless ocean. Reaching out his arms, again and again he prayed to his dear mother:

“Mother! You gave me life, short as that life will be, so at least Olympian Zeus, thundering up on high, should give me honor—but now he gives me nothing (89 Book 1 line 410).

Achilles, despite his prowess and stature in the Greek army, is like every mortal doomed to suffer and die in this world, in a life destined to be cut short in the prime of his life. Like Gilgamesh, he spends the majority of the poem attempting to avoid his fate, this time using inaction and passivity as opposed to Gilgamesh’s course of action. Nowhere are these ideas of fatalism more apparent than Book IV, where Hektor states:

“Why so much grief for me? No man will hurl me down to Death, against my fate. And fate? No one alive has ever escaped it, neither brave man nor coward, I tell you – it’s born with us the day that we are born” (Book IV).

These morals continue into The Burial at Thebes, which pits an immovable object against an unstoppable force in the form of Antigone and Creon. Creon is our third character who realizes that he, like everyone, is a slave to the whims of the gods. He works tirelessly to thwart the actions of the unflinching Antigone, who will go to her death before sacrificing her principals. It is only when he is warned by the blind seer Tiresias that he relents, only to find that he is already doomed from the start. As Chorus almost prophetically states:

Whoever has been spared the worst is lucky. When high gods shake a house that family is going to feel the blow generation after generation… O Zeus on high, beyond all human reach, nothing outwits you and nothing ever will. You cannot be lulled by sleep or slowed by time (39 Heaney).

The stories though markedly different are vastly alike in their fatalistic view on life. In the worlds of Gilgamesh, Enkidu, Achilles, Patroclus, Antigone, Haemon, and Creon, choices are not made so much as carried out by performers on a stage. Their heroes is not to seek after riches or some magical item to reverse time, but to come to the realization that life is hard and death is inevitable… no matter who you are. As Lemony Snicket would say:

“The sad truth is, the truth is sad” (Hostile Hospital).

Works Cited

Homer. The Illiad. Trans. Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin, 1998. Print.

Snicket, Lemony. Horseradish. New York: Harper Collins, 2007. Print.

Snicket, Lemony. The Hostile Hospital. New York: Harper Collins, 2008. Print.

Sophocles. The Burial at Thebes: A Version of Sophocles’ Antigone. Trans. Seamus Heaney. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004. Print.

The Epic of Gilgamesh. Trans. Andrew George. New York: Penguin, 2003. Print.