Ignorance is Bliss

In the latter end of the 3rd century BC, Solomon, King of Israel wrote down his philosophy on the meaning of life,

“…And I set my mind to know wisdom and to know madness and folly; I realized that this also is striving after wind. Because in much wisdom there is much grief, and increasing knowledge results in increasing pain.” (New American Standard Bible, Ecclesiastes 1:17-18).

Agree or disagree, the above statement holds truth in regards to the passages explored thus far, specifically Two Ways of Seeing a River by Mark Twain, Learning the Language by Perri Klass, and Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. The focus of this essay will therefore, not examine style so much as this omnipresent theme, that knowledge and realization are sometimes equated with sadness.

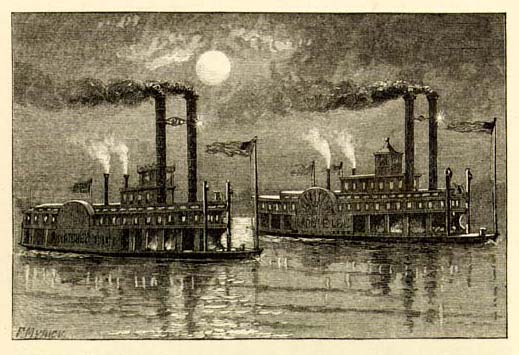

Nowhere is this more apparent then in Two Ways of Seeing a River, in which Twain, at this time in his life, a steamboat pilot working along the Mississippi river, laments having traded his initial wonder and awe at the natural beauty of the river for benign observation. He describes his first encounter with the river as if he were acting out of reverence towards God himself.

“…the lights drifted steadily, enriching it every passing moment with new marvels of coloring. I stood like one bewitched. I drank it in, in a speechless rapture. The world was new to me and I had never seen anything like this at home” (Twain 1).

Twain is well known for his fine prose, but here his flourishes are poetic. It’s as if he’s scrounging every word in his expansive vocabulary to describe his emotions but can’t, so in desperation he throws everything he’s got into this passage with the passion and pent up emotion of a 70’s punk rock singer. But halfway through the narrative, his tone shifts from one of astonishment to a heavy, weary, nostalgic, sadness.

“…I began to cease from noting the glories and the charms which the moon and the sun and the twilight wrought upon the river’s face; another day came when I ceased altogether to note them” (Twain 1).

What has happened? Employment on the ship has forced our hero to sell his feelings for thoughts. His relationship with the river goes from an admirer to that of an associate. To him, the river represents a mechanism, something that is used rather than viewed for the sake of viewing.

“No, the romance and beauty were all gone from the river. All the value any feature of it had for me now was the amount of usefulness it could furnish toward compassing the safe piloting of a steamboat” (Twain 2).

Twain speaks as if he’s confessing to a crime in an attempt to wash his hands of guilt. By obtaining the knowledge necessary to run and operate a steamboat, he has traded an inborn asset, his innocence.

The entire scene becomes so demystified that even his choice of words is flat and professional, which happens to be the very subject of Learning the Language by Perri Klass. Not unlike the Twain piece, this passage follows Klass as she begins a fledging new job in the medical practice.

“I learned a new language this past summer. At times it thrills me to hear myself using it. It enables me to understand my colleagues, to communicate in the hospital” (Klass).

Again similar to the previous author she experiences the thrills of being lost in a totally new environment, experiencing something to unknown and foreign. She uses the choice word: enable, to suggest that without this new found knowledge she could not hope to survive in this world, exactly as Twain would never have been able to hold his position as a pilot without an intimate understanding of the river. However, she continues:

[I] find that this language is becoming my professional speech. It no longer sounds strange in my ears-or coming from my mouth. And I am afraid that as with any new language, to use it properly you must absorb not only the vocabulary but also the structure, the logic, the attitudes (Klass).

Klass reveals that with the acquisition of knowledge comes familiarity, and eventually adaptation. She puts forth that not only does one give up mystique with mastery of a subject, but also that that comprehension changes a person’s identity. Because being an observer and a participant are mutually exclusive, Klass has to sacrifice one for the other.

“At first you may notice these new and alien assumptions every time you put together a sentence, but with time and increased fluency you stop being aware of them at all” (Klass).

The narrative leaves the question of whether or not the change is ultimately worth it, decidedly open, but it does state that the transformation happens so gradually that the participant doesn’t realize they’ve lost something until it’s gone. This reinforces the theme of these texts that knowledge often goes hand in hand with an inescapable feeling of sadness and nostalgia.

Plato’s take is perhaps the most poignant. He paints the picture of life-long prisoners in a cave filled with nothing but darkness.

“Behold! Human beings living in a underground cave, which has a mouth open towards the light; here they have been from their childhood, and have their legs and necks chained so they cannot move…” (Plato).

The sad inhabitants of this cave, know nothing except about the world that is the cave itself. Unlike the Mississippi River, there is no obvious beauty apparent in this place. Neither is there the excitement that was found in Klass’s personal experience. It seems that the prisoners in this reality have nothing to look forward to in their existence except the possibility of escape. Plato however, sheds an important light on this notion.

At first, when any of them is liberated and compelled suddenly to stand up and turn his neck round and walk and look towards the light, he will suffer sharp pains; the glare will distress him, and he will be unable to see the realities of which in his former state he had seen the shadows… Will he not fancy that the shadows which he formally saw are truer than the objects which are now shown to him? (Plato).

This famous allegory draws many comparisons and interpretations, and the author of this paper would be quite foolish in assuming that it’s only application is to his thesis. That being said, what does light do in Plato’s cave? It illuminates, and it reveals what was previously hidden. The light is the physical embodiment of any knowledge. Do humans not all start their lives in a cave? Gradually they grow, they adapt, and things become expected of them. They shed their youth, their innocence, and must become adults.

These texts don’t seem to suggest that it would be better or even possible to avoid having one’s mind expanded, changed, and molded. But they do shed light on the sad truth that growing, learning, and progressing in life are a painful experience. While the learned thinking man, might at times regret his decision to leave the comfort and security of the cave, he cannot go back. His only option is to move forward, where hopefully he’ll discover a new vista, and with it his sense of wonder.