The Lost Scientist

The Lost Scientist

“Everybody’s a mad scientist, and life is their lab. We’re all trying to experiment to find a way to live, to solve problems, to fend off madness and chaos.”

-David Cronenberg

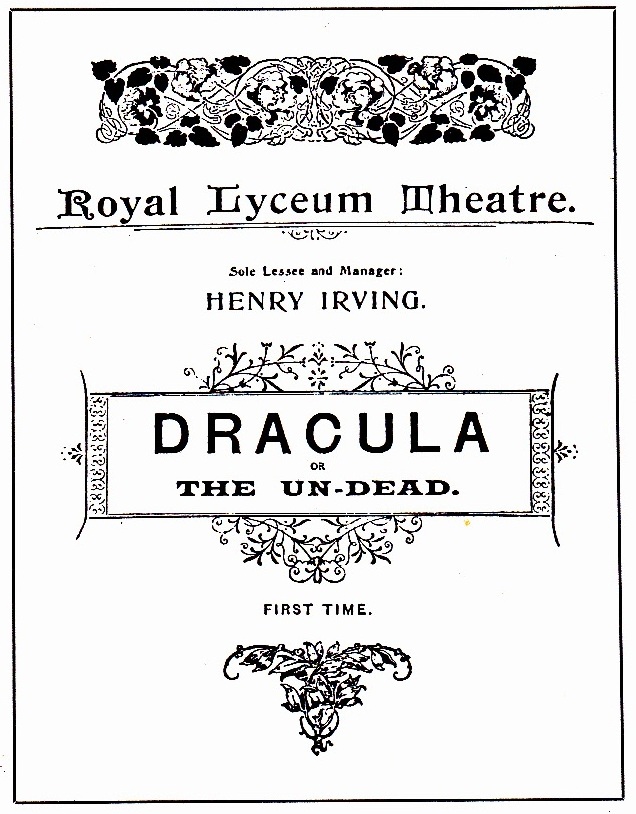

There is a particular movie hero that is lost to time, that existed briefly, flourished and then vanished at the dawn of the 1960’s, never to be seen again—the 50’s B-Movie Scientist. Movies change. The tides ebb and flow, the moon waxes and wanes, presidents come and go, and even movies aren’t the same as they were. In the 1950’s the landscape of film was steeped in the atomic age. Suddenly Dracula, Frankenstein, the Mummy, and their friends weren’t scary anymore—we needed monsters that were capable of conquering the entire world, whether they were aliens, science experiments gone awry, or a gorilla wearing a space helmet (that last one actually gets the closest out of any of them).

But man has fought monsters on film for as long as movies have existed, Thomas Edison himself was responsible for some of these early… let’s be charitable here film experiments. But there is one thing that sets the horde of 50’s shlock B movies apart from the rest of the crowd—the scientist hero. It has long been my theory that each decade espouses its own movie hero, its ideal, its Charles Atlas for us to look up to. In the 30’s and 40’s we had the jaded detective (Maltese Falcon, Dark Passage, The Big Sleep) in the 80’s thanks in large part to WrestleMania, the testosterone and the violence was pumped up, suddenly, we needed action heroes who weren’t just mentally up the task but physically too (Predator, Robocop, Commando, First Blood).

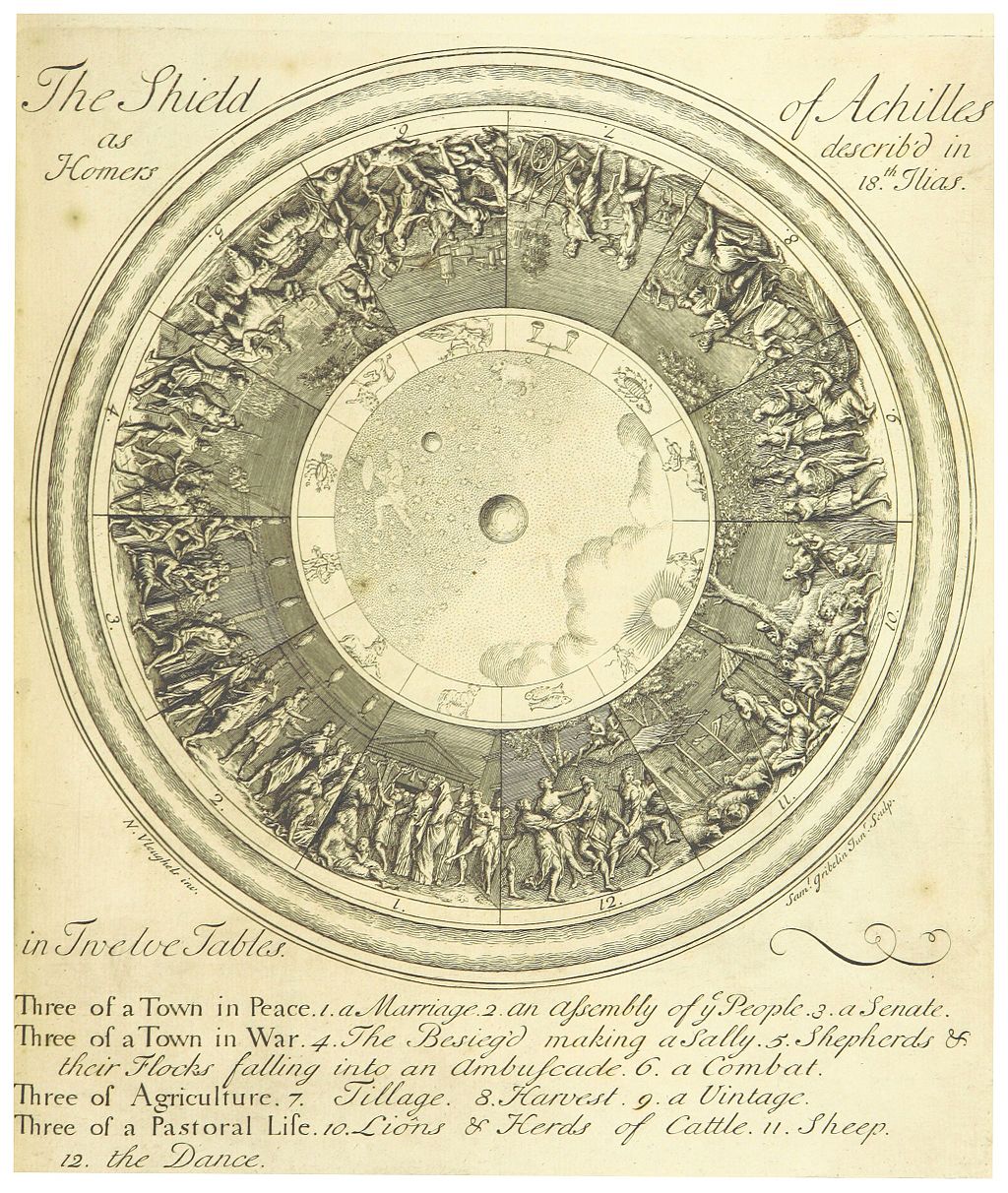

This smoothed out in the 90’s into the more relatable everyman protagonist (Lethal Weapon, Die Hard) who still had to kick ass but was emotional, unsure of himself, and had a down to earth personality. All of this leaves the peculiar brand of 1950’s scientist heroes oddly alone. It would not be hard to imagine a scenario where Sam Spade would share drinks and stories with Robocop and Roger Murtaugh, but what about Dr. Cal Meacham from This Island Earth, Dr. Miles Bennell form Invasion of the Body Snatchers, or Commander John J. Adams from Forbidden Planet? They are in some ways the spiritual successors of Arthur’s Knights, with the stiff upper lip of the British mixed lovingly with the cocksure bravado that comes with being American. But that alone is not what makes them different.

In the decades before, Raymond Chandler would lay out the qualities the ideal hero would have to possess; “He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor—by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world.” The heroes of the atomic age were no different, but we saw fit to add one more crucial quality to the formula—raw intelligence.

Dr. Miles Bennell was likeable, smooth talking, and honorable to be sure, but he came equipped with intellect, deductive reasoning, and a PhD in Psychology. He is an analyzer not a man of action, his chief weapon against the aliens is his brain.

“Maybe they’re the result of atomic radiation on plant life or animal life. Some weird alien organism—a mutation of some kind… whatever it is, whatever intelligence or instinct it is that

govern the forming of human flesh and blood out of thin air, is fantastically powerful…All that body in your cellar needed was a mind…”

Miles is by no means an isolated case, looking around the veritable explosion of science fiction films of the time reveals almost nothing but doctors. The Fly’s Andre Delambre, the unnamed Professor from Robot Monster, the entire horde of scientists’ aboard steamboat Rita in Creature from the Black Lagoon, noble scientists were as viral as the chicken pox—but why?

Why for an entire decade of film history was the average American in love with the idea of a scientist hero, who wore lab coats instead of fedoras—I have a theory. When the nightmare that was World War II ended America now looked for new terrors, threats beyond our solar system, the fear of technology gone awry, but there was something else—a hope for a new kind of lifestyle, and a new kind of man. If the monsters in these movies represented our fear and paranoia, the scientists represent mankind’s perseverance, intellect, and ability to reason.

All of these films would pave the way for the next generation of sci-fi heroes. The negative and ugly sides of scientific progress would fall by the wayside, as Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek would go on to focus on the idealism and the romance of the cosmos. James T. Kirk would embody the smarts and heroism of his ancestors, but he was never corrupted, never succumbed to some horrible fate, and always preserved in the face of evil.

Through all our existence, the frightened and faint hearted have been warning men not to push any further, not to learn any more, not to hope grow, and exceed themselves. I don’t believe we can stop I don’t believe we’re meant to… I must point out the possibilities, the potential for knowledge and advancement is equally great. Risk is our business.

By the time the 70’s rolled around, the mantle of sci-fi hero passed from Kirk to Skywalker, whose intellect took a back seat to spirituality—but the idealism remained. The lone scientist hero may indeed seem a pastiche from a bygone era, but their spirit lives on. The Scientist and his reluctance to violence, slowness to anger, and intellectual pursuits can still be seen today, in the forms of Tony Stark, Bruce Banner, Dr. Stephen Strange, and other Marvel mainstays. They are, if anything else, a reminder to analyze our surroundings, to question authority, and to fight back against the unknown till our knuckles bleed and our life spark goes out.

“Alta, about a million years from now the human race will have crawled up to where the Krell stood in their great moment of triumph and tragedy. And your father’s name will shine again like a beacon in the galaxy. It’s true, it will remind us that we are, after all, not God.”

-Forbidden Planet