Little Miss Prometheus

The Shape of Things is a look at the moral choices an artist is faced with, and what is within the limits of acceptability. President John F. Kennedy shared his thoughts on the matter when he addressed Amherst College:

“If art is to nourish the roots of our culture, society must set the artist free to follow his vision wherever it takes him” (“President John F. Kennedy: Remarks at Amherst College, October 26, 1963”).

His points are indeed valid, but they raise an interesting question — what if the artist had to hurt someone to meet their goals? Should they be allowed to proceed if it meant creating a masterpiece?

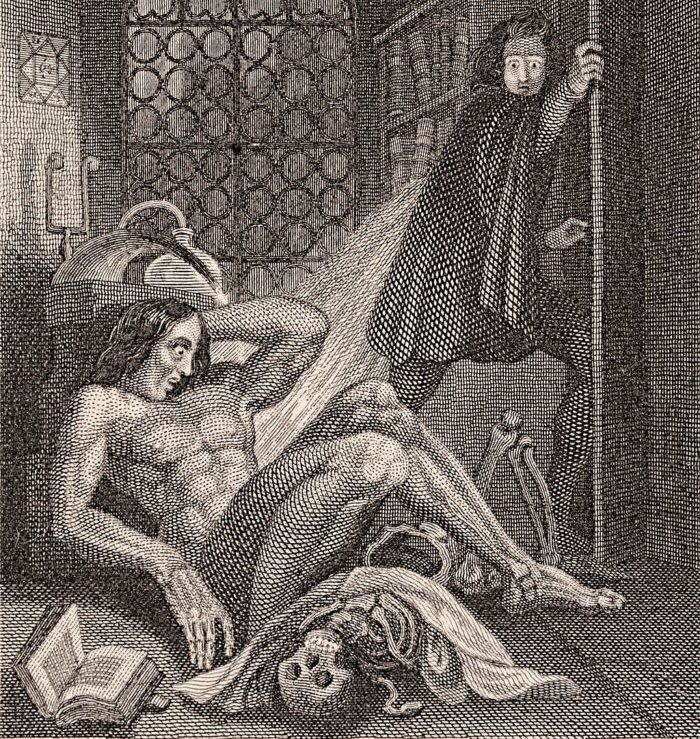

This is the subject of Labute’s rather incendiary play, The Shape of Things. When analyzing this most complex work, it is impossible to overlook Evelyn, perhaps the most fascinating and mysterious of the four lead characters. An intensely beautiful, spontaneous and seemingly open person, she begins dating Adam, a dumpy, sad sack loser and begins to subtly change his life. She dominates Adam both physically and intellectually, turning him into a beautiful hunk of a man over the course of a wardrobe overhaul, plastic surgery, and by forcing him to sever all ties with his former friends. All of this seems expected if not a bit hasty, that is until she reveals that it was all an elaborate façade, that Adam is merely an art project for her, and that she harbored no feelings for him whatsoever—all so that she could see if Adam could be transformed the same way clay is shaped into a sculpture. It is here that Eve’s already complex character begins to become even more labyrinthine. The question arises, did she go through all of these lies simply to wound an innocent man, or is she truly creating art? According to Oscar Wilde’s chilling novel, The Picture of Dorian Grey the answer to the latter is an affirmative yes. Oscar Wilde explained,

Those who find beautiful meanings in beautiful things are the cultivated. For these there is hope. They are the elect to whom beautiful things mean only Beauty. There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all (xii).

Had Oscar Wilde been in attendance at the climax of the play, The Shape of Things, he certainly would have come to a different verdict than most of the principal cast—despite the unconventional means, Adam has become a most fine work of art, and to Wilde that is all that is important. With Dorian Grey as the Exhibit A, this essay will examine Eve’s actions through Wilde’s unique point of view, and determine that they are justified in the realm of art.

Even before Eve is unveiled as the true renegade that she is, she begins showing signs of her loyalty to art over social norms as early as the first scene as she is about to deface a statute in a public museum where Adam works as a security guard. Adam approaches her:

“…[Y]ou stepped over the line. [M]iss? / [U]mmm, you stepped over…” And Eve responds, “I meant to. / [S]tep over…” Adam continues, “[W]hat? / [Y]eah, [I] figured you did. [I] mean, the way you did it and all…” And Eve interjects, “[I] know, / [T]hat’s why I tried it” (1).

Eve, much like her biblical namesake, has already established herself as a rebel, and has her own artistic agenda, even if it conflicts with legality or morality. Such actions might be seen as off-putting, but through the lens of an artist such as Wilde, these actions are not only acceptable but also necessary to create good art. From that standpoint, she is not defacing art but is resurrecting it from cliché. The morality may be in question, but her artistry cannot be detested, and as Wilde has pointed out, the former should not even matter to a perspective audience.

Adam allows Eve to alter the statue as she sees fit, which is the first in a long chain of events involving him submitting effortlessly to her will. With Adam as the only witness to her actions it seems innocent enough, but then the couple rub shoulders with Adam’s friends and then Eve feels put upon to defend her seemingly anachronistic motives against Adam’s bullheaded friend Philip, when he begins defaming the anonymous graffiti artist in the museum who we of course know to be Eve:

“[N]o seriously, do you believe that shit? [S]somebody with the gall to do that kinda bullshit on our campus? [T]hat fucking burns me up…”(31). To which Adam responds, “…[I] understand the impulse… [I] don’t think it was just kids playing, [I] think it was a sort of statement…” (31).

Here Eve’s morals are once again put on trial and scrutinized by all except her subservient lover. She does a fair job of countering all of Philip’s arguments but she still comes off as narcissistic and pretentious to readers—especially with those familiar with the play’s shocking twist ending. It is through Wilde’s strikingly similar companion piece, that Eve’s actions take on credibility. Wilde builds a similar debate of the importance of beauty over morals in The Picture of Dorian Grey, here the hedonistic Lord Henry coaches’ Dorian Grey, a beautiful but naïve youth on his life philosophy on beauty:

…[Y]ou have the most marvelous youth, and youth is the only thing worth having… You have a wonderfully beautiful face, Mr. Gray. Don’t frown. You have. And Beauty is a form of genius—is higher, indeed, than Genius, as it needs no explanation (16).

Regardless whether it is his superior prose or his beautiful choice of words, through Wilde’s book, Eve gains more traction. Lord Henry’s support for beauty and pleasure over all else is in the exact same vain as Eve’s point of view, and if indeed beauty is rarer and more richer than morals or intellect, than in the end Eve has given Adam a gift that far exceeds the means taken to achieve them— whatever the repercussions may be.

Eve, in her mind is creating a fantastic human masterpiece, foregoing pencil and paint for more discreet tools such as sex, lies, manipulation, persuasion, and subtlety. To Eve, how the art is created is not nearly as important as the quality of the art itself. But Adam is still blissfully unaware of what is happening behind the scenes, for him the trim new physique and wardrobe are simply the icing on the cake of his newfound relationship. However, his unquestioned loyalty to Eve is put to the ultimate test, when she gives Adam a harsh ultimatum. Either put aside his friendships with Philip and Jenny or lose her forever.

Morally speaking, her actions are unacceptable but to Eve this is the quintessential finishing touch on her tour de force, not even a necessary evil—just necessary, because for the sake of beauty they are rational. Adam’s acceptance of the proposition is his final downfall, he has partaken of the fruit, and there is no going back to the Eden he left behind. Following the Bible story from which his name originates, Adam is about to realize the difference between paradise and the real world.

On the night of her art presentation, Evelyn reveals the deception that she had been pulling over Adam’s eyes throughout the entirety of the play. The confrontation afterwards between the two stands as the highlight of the entire story, Adam verbally attacks her, going so far as to call her a “heartless cunt,” but like Wilde and Lord Henry, Eve is willing to justify her actions. She responds blissfully:

“All that stuff we did was real for you therefore it was real, it wasn’t for me therefore it wasn’t. It’s all subjective Adam—everything” (123).

In Eve’s mind she has done no wrong, the world to her is merely art; morality has no place in art. Adam on the other hand cannot see himself that way, he is a person, and he has just been robbed of a waking dream to escape his painful reality. Neither of these perspectives is wrong, just different, but if Adam were to take the side of Eve or Lord Henry he might see the bright side of the situation. Because according to Oscar Wilde:

“Behind every exquisite thing that existed, there was something tragic. Worlds had to be in travail, that the meanest flower might blow…” (26).

Oscar Wilde would look upon Adam and see him as nothing more than a beautiful flower in full bloom, and though he has endured a harsh winter, that was only so he could enjoy a peaceful spring. But as John F. Kennedy could attest to, sometimes spring is short lived.

�Works Cited

Labute, Neil. The Shape of Things. New York: The Broadway Play Pub, 2003. Print.

“President John F. Kennedy: Remarks at Amherst College, October 26, 1963.” National Endowment for the Arts. Web. 15 December 2014.

Wilde, Osacr. The Picture of Dorian Grey. New York: Dover Publications, 1993. Print.