Arthurian Seasons

“And so, perhaps, the truth winds somewhere between the road to Glastonbury, Isle of the Priests, and the road to Avalon, lost forever in the mists of the Summer Sea.”

-The Mists of Avalon, Marion Zimmer Bradley

As the embers of the bonfire flared before my character in Dark Souls, I exhaled stress and breathed in relief. I set the controller down—it was time for a break. My mind began to drift, and I began asking myself “Why do I do this? Why do I do anything?” It seemed to me that most of what I did, in school, in work, and in relationships was Sisyphean in nature, requiring so much effort for little to no payoff. Sadness consumed me, it seemed year after year I was losing my idealism layer by layer like a snowman left out in the rain. Then it hit me… I was like one of Arthur’s knights in a way.

We wander strange paths in this life we call home. Our quest for meaning seems to begin as soon as we leave the womb, agitated and acutely aware to our first new sensation—discomfort.

Strangest of all though, is what we do after the halcyon days of childhood. Faced with an uncaring world and a seemingly indifferent universe, most of us turn to art & entertainment to help soothe us. But is our art so different from the chaotic lives we lead?

While there is a continual glut of safe, conventional, sitcom TV to pacify us, the remarkable thing are the stories that endure for centuries. What really seems to beguile us are the open-ended stories, tales that refuse to give us closure, the ones with dreams that stay distant, like the green light at the end of Gatsby’s pier, Kane’s sled burning in the fire, it is the leopard that sits atop Kilimanjaro seeking who knows what—it is the yearning for more. In his last play The Tempest, Shakespeare wrote:

“Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind.”

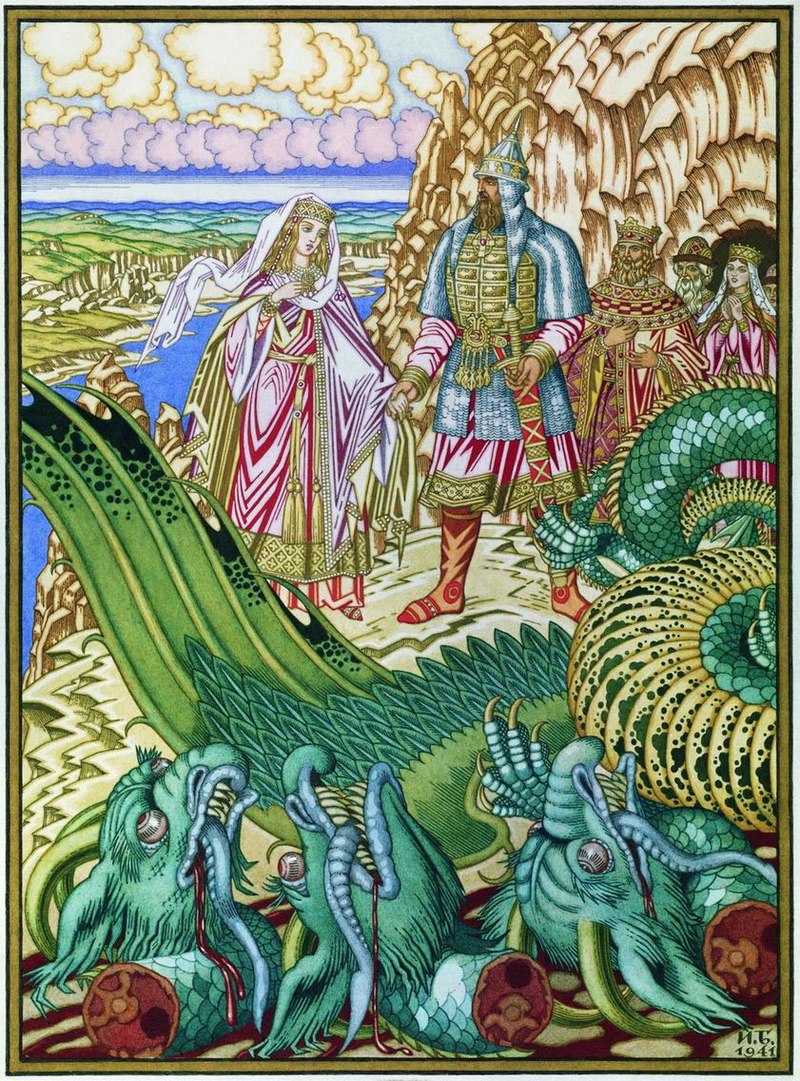

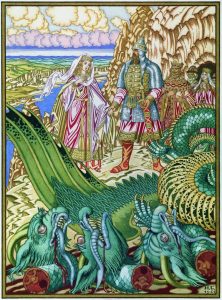

It would seem, we humans have a strange fascination with the questions we seem to have no answers to, the puzzles that are unsolvable, and the journeys that go on indefinitely. It’s why we play Dark Souls even though we die, die, and die again and why we love Game of Thrones even when our favorite character is beheaded… But long before From Software’s Dark Souls was formed, before F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote the last lines to the Great Gatsby, and before even the Bard himself lived, there was another story about an endless quest—the Arthurian Legend. In many ways it is the bedrock of our modern-day stories, containing the romance of a bygone period, flights of fantasy, and the nightmare of reality. So how did echoes of it end up in Dark Souls? And what exactly is the moral, if any of this rather sad story? We must go deeper.

Strange Heroes and Unheeded Warnings

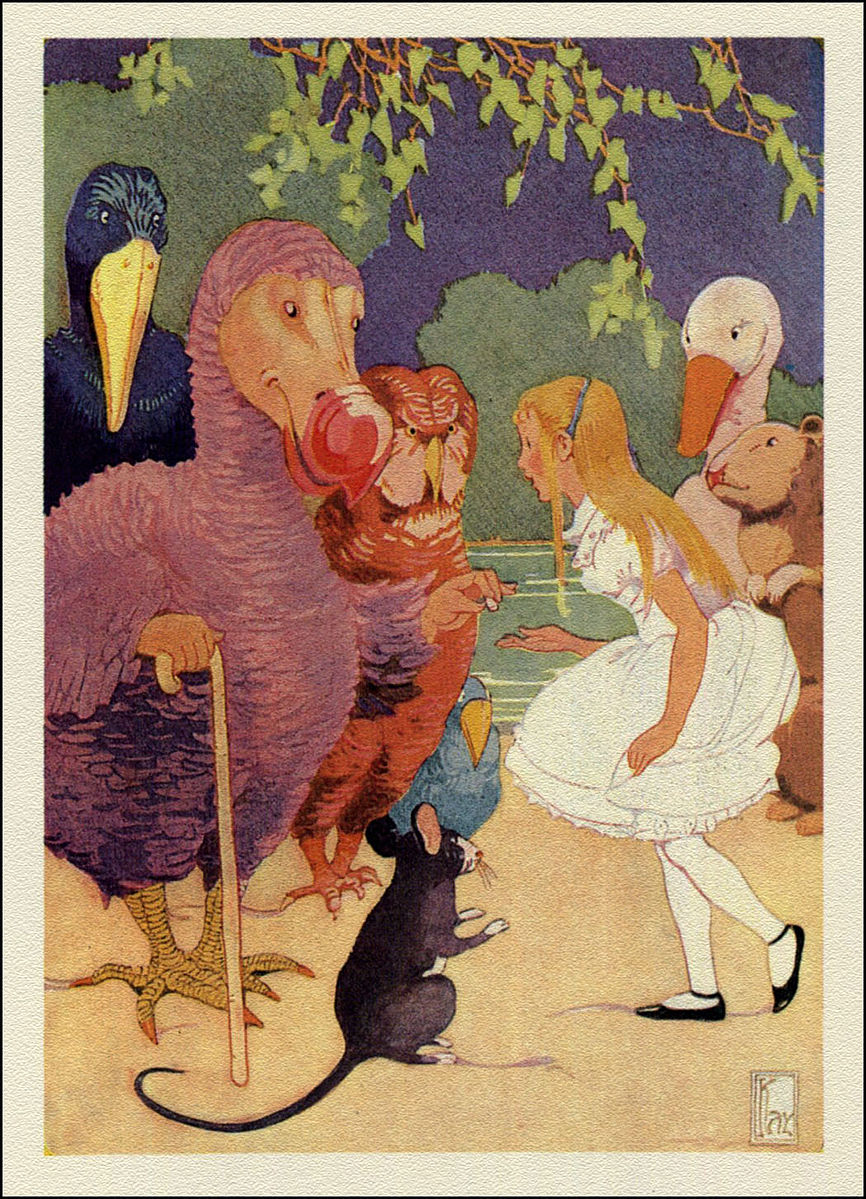

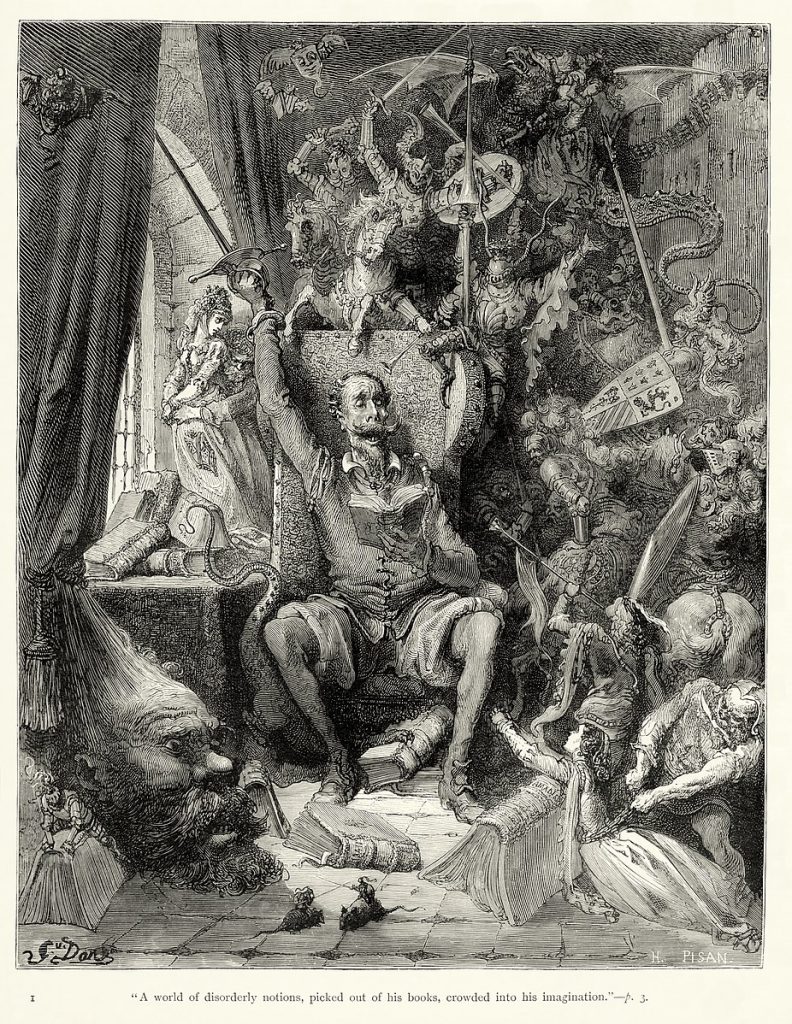

The many stories that surround Arthur come from different authors, across various languages, countries, and time periods (with the majority emerging from the late 11th the 13th centuries) but it wasn’t until Chretien De Troye’s Story of the Grail, that the titular Grail was introduced as the end all be all quest…and more importantly it shifts the mantle of hero from Arthur to another knight—Percival. Whereas Arthur was cunning, intelligent, and up to task, Percival is described as something of a hayseed, a dirty peasant who isn’t even aware of what a knight is. As Crash Course History’s Mike Rugnetta puts it:

“[Percival] is maybe not the kind of knight you’re used to, he’s a very brave young man but he’s not the sharpest lance in the armory… it also turns out his chivalry and naiveté play big parts in his Hero’s Journey. When our story begins Percival is living alone with his mom in the Waste Forest… which sounds unpleasant”

My mind went back to Dark Souls, my own hero and yet another connection to the Arthur myth. He looked more like a putrefying corpse that happens to walk upright—hardly anyone you’d expect to take up a heroic pilgrimage. And like Percival, our Chosen Undead arrives not in a glamorous wonderland but in a wasteland—a place that needs healing. On top of all that, instead of a wise old sage, the only mentor the Chosen Undead has is a sardonic and mean-spirited wanderer who has given up on life.

“Well, what do we have here? You must be a new arrival.

Let me guess. Fate of the Undead, right? Well, you’re not the first.

But there’s no salvation here. You’d have done better to rot in the Undead Asylum… But, too late now. Well, since you’re here… Let me help you out..”

This is for better or worse, your call to adventure. No grand heroic tidings or princesses are promised you—you’re only warned. The Chosen Undead may not look the part, but he certainly acts it. Despite the sensible warnings of the Crestfallen Warrior, he pressed on towards an uncertain and mysterious goal—maybe out of an absurd desire, perhaps just because there aren’t other options given you.

All of which mirrors Percival’s own call to adventure. After discovering that he indeed is of noble heritage, he sets off on his own quest. But Percy’s mother is a woman of sorrows, acquainted with grief. Her husband and Percival’s brothers were knights who were killed in battle—and so now she must confront him about the real down-to-earth dangers of knighthood—the nightmares of reality.

496 His mother did all she could

497 to keep him there and make him stay

498 while she prepared his trappings:

506 but she could only keep him three days, no longer!

507 Her cajoling became useless.

508 Then his mother was seized by a strange mourning.

509 In tears, kissing him, embracing him,

510 she said, “I feel very sad

511 my beloved son, seeing you leave.

512 You will go to the King’s court,

513 and you will ask him to give you arms.

514 He won’t argue,

515 he’ll give them to you, I’m sure.

516 But when the time comes to bear them

517 and to use them, what will happen then?

518 How will you succeed

519 in something you have never done,

520 nor seen another do?

In our minds quests always have happy endings, but in the real world, in Arthurian tales, and yes even in Dark Souls—the truth is that quests are dangerous, ill-advised, and often result in failure. But perhaps that’s just it, we need something that we’re willing to die for… or perhaps live for is the better way of putting it. The aesthetic distance between art and reality was closing in on me.

With these warnings our quests almost seem too foolhardy to even attempt. It was beginning to get harder and harder to separate myself from my player character, and from Perceval himself. Was the Chosen Undead the insane one for wanting to continue on, or was I the one forcing us to wander into a strange questline? After all who was making the decisions here? I reflected back on what brought me to these thoughts… relationships that stifled and disintegrated, unrequited love, questions of my own faith, existence, all things that seemed to recede into the mist like the holy grail itself—leaving not a rack behind.

Sacrifices and Unhappy Endings

It’s the late 1990’s, I have a portable TV set, and a stack of VHS tapes from which to choose, but among those, one is my personal favorite, it wasn’t Disney, it wasn’t even animated, and it certainly wasn’t for children—but that didn’t stop me. When you started the film, you were greeted by amazing music and white titles on a black background that read:

England

932 A.D.

Shimmering dark grey mists rolled over green terrain, the sound of hooves, and out of the fog came two men, one hunched and filth covered (I would one day look up to the actor playing this man as one of my all-time heroes, but for now I just see him as a guy covered in shit) the other, is regal, bearded, and wears a crown. It should be noted however, that they are not mounted on horses but are pantomiming riding horses (my mom explains to me that it’s a joke, I don’t know if I quite understand but it’s still fascinating) and the sound of hooves is actually the filth covered man banging halves of coconuts together. The film as you might have guessed, is the 1975 classic Monty Python and the Holy Grail, directed by Terry Jones & Terry Gilliam, and it was both my favorite film and my first exposure to King Arthur, his Knights, Camelot (a silly place), and the Holy Grail.

I loved that movie, for me it was pure escapism—and somehow it all managed to be funny even though not a single person in that film acts anything but deadly serious. I didn’t have a clue who Monty Python was or what he had to do with the movie, but who cares when the story is so wonderful? However, there was one thing I never understood about that film. It baffled me for years and seemed oddly out of place (even for a movie with a flying killer rabbit)—it was the bizarre and anticlimactic ending.

Arthur has only one surviving knight, Bedivere the wise, as the two make their way on a ghostly ship to a castle on a lake where the Holy Grail is being held. They arrive at the front entrance… whereupon they are greeted by having shit dumped all over them from the battlements by their mortal enemies—the French.

They slink away, and amass a large army out of seemingly nowhere, and are about to lay siege to the French, and recover the grail once and for all—they charge.

“French persons! Today the blood of many a valiant knight shall be avenged. In the name of God, we shall not stop our fight till each one of you lies dead and the Holy Grail returns to those whom God has chosen”

They charge. All of a sudden modern-day policemen show up, arrest King Arthur without a word, and shut down the films production. That’s it. My favorite movie builds to a grand finale but just ends without a word or any sign of resolution.

Little did I know that this is quite literally how all stories about Arthur end. Not with a bang but with a whimper. Story of the Grail, the text that introduces the Grail, ends abruptly in the middle of Percy’s quest, Chretien De Troye never even finished the story. Perceval learns the truth about the Grail, that in his questing he caused his mother to die of grief—and now must seek penitence for his selfishness—and then nothing. We never see his quest all the way through. It turns out that the funhouse mirror version of Arthur’s Knight found in the world of Monty Python is actually a replica of how his adventure really ended.

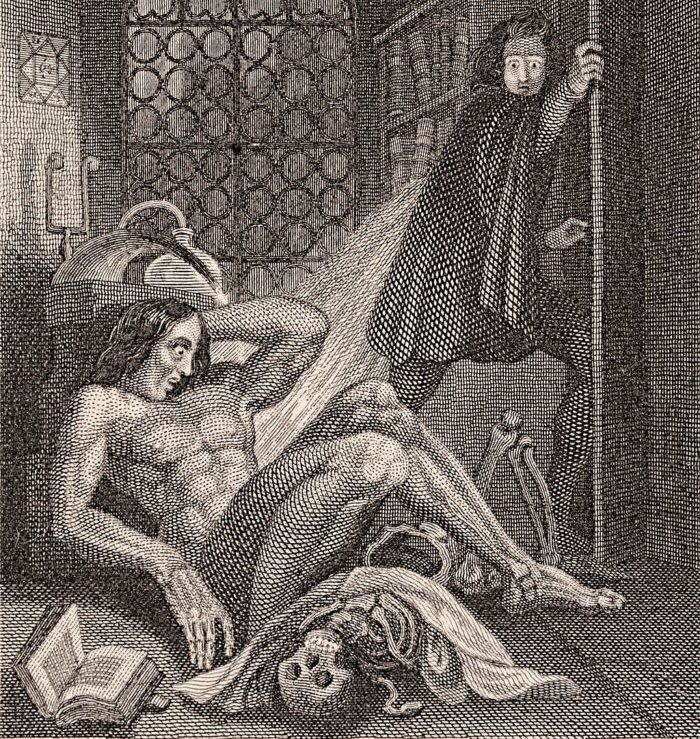

While Percival’s story is sad, Arthur’s tale is downright tragic. In Sir Thomas Mallory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, after pages upon pages of Arthur trying to put down the usurper, Mordred (his own son), he crowns himself king right under Arthur’s very nose. It is at this point that Mallory himself chimes in to offer his own sorrows.

“Lo, ye, all Englysshemen, se ye nat what a myschyff here was? For he that was the moste kynge and nobelyst knyght of the worlde, and most loved the felyshyp of noble knyghtes – and by hym they all were upholdyn – and yet myght nat thes Englyshemen holde them contente with hym. Lo, thus was the olde custom and usayges of thys londe; and men say that we of thys londe have nat yet loste that custom.” (680.25-31)

Mallory places the blame on Arthur’s political defeat on mankind’s longing for “new fangill”or in modern day speak; preferring novelty to the status quo, and fads to the long-standing tradition. In effect, Arthur loses his throne due to being too good and far too conventional—which sounds sadly none too different from our own times. The values that were the bedrock for Arthur’s Kingdom are thrown out and replaced by evil—in the end it wasn’t an invading army or a horrible monster that uprooted Camelot, it was mere boredom.

But what does any of that have to do with Dark Souls, and my own life? Your own Chosen Undead’s choices aren’t much better at the end of your quest. Either light a bonfire that enables dying gods to continue to wilt for another century or so until another usurper takes over your spot, or let the flame die out and let the age of men begin, ushering a short time where you are now king—but again that only lasts until the next cycle, where a new Undead will have to do the exact same thing—are we stuck in a pattern? After all, Arthur’s kingdom fades away not long after he dies, quickly corruption spreads into his court and his age of chivalry gives way to greed. So, if quests are in vain, only cause grief, and seem bound to fail no matter how long the good times last… then the real question is, why even bother?

Resurrection and the Hope that Remains

It’s 2014, and I haven’t been in America for a long time now. I teach English in the city of Hradec Kralove, East of Prague. My students are a group of extremely enthusiastic young people, some have even said I changed their lives and that I’m their best friend. I care about all of them, but one of them stands out from the rest. She’s 18 years old, with jet black hair, glasses, pale skin, and almost always wears slick stockings—her name is Susan. It’s an open secret that we’re in love with each other, the students know, the other teachers know—everyone knows. Even Adam, the strict by the books Englishman who’s assigned to watch over me, if anything overtly romantic happens between Susan and me, he’s the one to turn me over to my boss. Maybe it’s because Adam was my best friend at the time, and that after years of abuse from our fellow staff he finally had found someone who he could be himself around. Regardless of his reasons why, he never says anything to anyone. The truth is, that everyone loved Susan. When she walks into the room, I can hear other students whisper under their breath how bewitched they are, and even the other teachers, none too subtlety allude to her attractiveness. For whatever reason, she sees past them all and chooses to spend her time with me. For a few months, things are bliss. But something does happen—they decide to transfer me hundreds of miles away.

I’m not happy. That night I’m bombarded with phone calls and texts from students and friends to find out if I’m leaving—they take the news better than I do. Susan sends me a vague text saying she has one final gift for me… my fellow staff and I all wonder what it could be. I’ll find out soon as I wait for her, wearing my red wool hat so she’ll find me in the crowd. Susan finds me in no time, hugs me, and presses a letter into my hand. We talk about things I can’t remember, but it will be the last time we see each other for a very long time. She’s heading to Paris, and I’m heading West to Moravia. When we part, Adam, who had been watching the whole affair, walks up to me and scolds me for hugging her—twice. I shrug it off, he has yet to make good on any of his threats. Later that week, he too would be saying goodbye to me—but he took it much harder than Susan did. Getting on the bus, I could see him out the window staring at me. He smiles at me and I realize that tears are streaming down his cheeks as his face turns red.

It sets in that I have not only lost the only girl who ever loved me, but three of my best friends, and a horde of students—most of whom I would find out, stopped going after I left. I pull out the iPod I smuggled for the five-hour journey, my boss thinks it’s full of good Christian Hymns but really, it’s loaded up with the Beatles, the song I play is She’s Leaving Home. As my bus leaves Hradec Kralove, I pull out the letter and begin to read. That was the Spring, before everything went so horribly wrong. I don’t know it yet, but I’m about to embark on three and a half years of depression, therapy, and hardship. I cling to that memory because it was the moment I knew that no matter what happens next, I had made Hradec Kralove a better place.

It’s the present once again, and my Chosen Undead has just killed the Lord of Cinder, my hours of toil, blood, sweat, and tears are done. I take a moment to drink it all in, after all, once I light that final bonfire it’s all over. After my character reaches his pale hand into the darkness and sets himself and the surrounding area on fire, I have only one question on my mind. “Now it’s time for Dark Souls 2”—that’s how I feel after every game, like I’m going onto the next story, group of characters, and land that needs healing. I think in his own way, that’s what Arthur thought as he lay dying on the Isle of Avalon, that perhaps he would one day return to bring his golden age back from legends into reality, but for now he has to go to the land of the dead. In the end, maybe our life’s journey isn’t to fix things forever but to make things better for a season, to experience wonderful springs, long summers, and tragic winters. As I close the book on another year, my mind goes to the words on Arthur’s gravestone.

Here lies Arthur, king who was and King who will be.